What Fugazi Can Teach Us About Web3 Fraud

Bootleg NFTs Don't Have To Be The Only Option

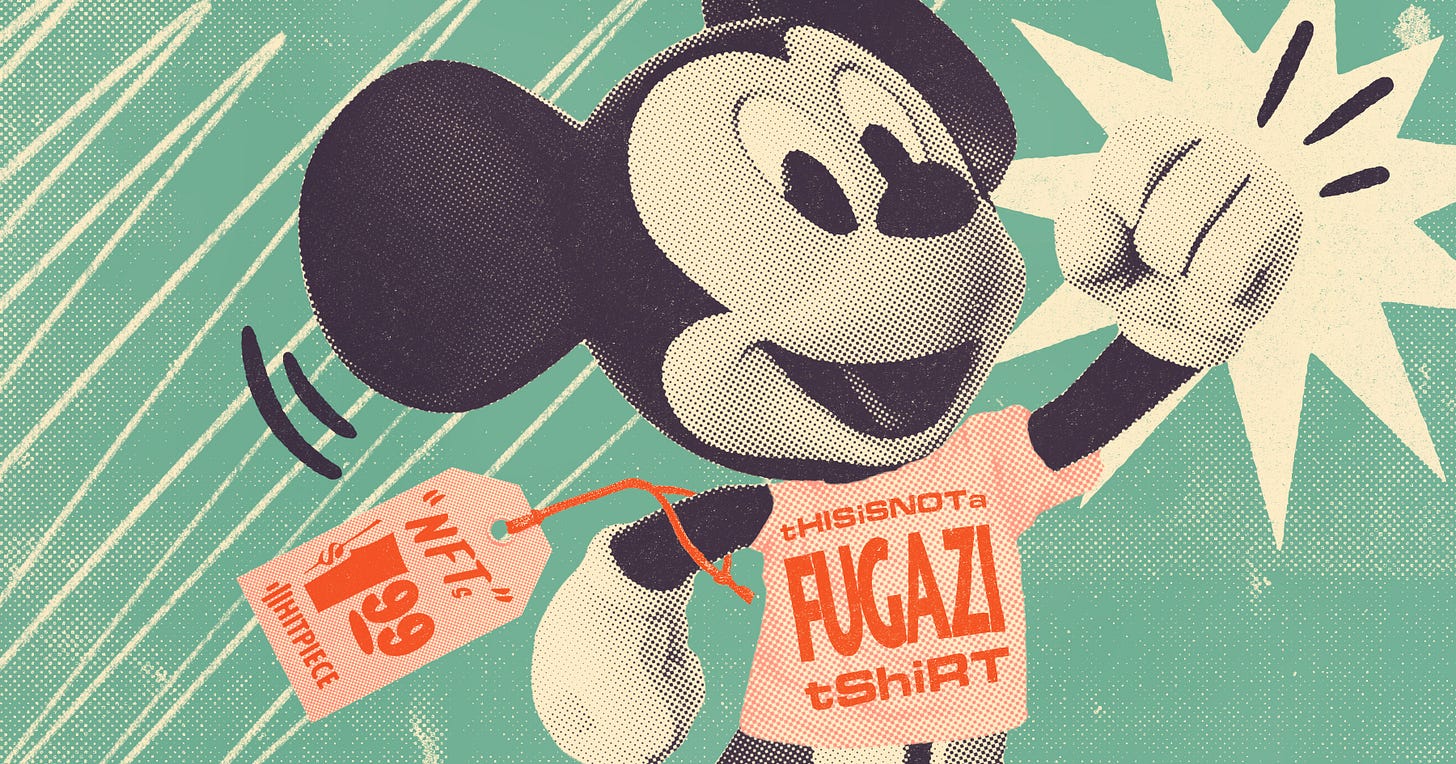

D.I.Y. legends Fugazi are famous for their $5 shows, $8 albums and strict no merchandise policy. But do a quick search on Etsy and you’ll find dozens of t-shirts, hat, patches and stickers with the band’s famous logo as well as the likeness of its iconoclastic frontman, Ian McKaye. There are even new productions of the infamous “This Is Not A Fugazi T-Shirt” t-shirts. On the internet, even the bootlegs have bootlegs.

The problem got so severe with McKaye’s band before Fugazi, Minor Threat, that in 2013, the singer authorized shirts celebrating the seminal straightedge hardcore band to be sold at Urban Outfitters. McKaye’s explanation was strictly pragmatic. In the absence of official Minor Threat merch, the bootlegging had gotten so bad that the only way to combat it was to license the logo to a manufacturer and let them stamp out the black market peddlers.

Except, nothing actually stops IP theft on the Internet. While music streaming delivered a healthy $5.9 billion in the first half of 2021 alone, piracy via torrents and other illegal download sites continues to thrive. Last week, Billboard ran an article titled Audius’ Next-Generation Streaming Service Is Plagued by Piracy, which detailed how the leading Web3 streaming platform, with 6.5 million users, fails to pay rights holders for the music on the service or offer even basic anti-piracy software to combat the issue of unauthorized uploads of content.

So it was hardly a surprise when the internet went apeshit over HitPiece, an NFT site founded by industry veterans Rory Felton and Michael Barren (ie. MC Serch of 3rd Bass fame), that appeared to be auctioning off unauthorized “music NFTs” of songs by every imaginable artist, from superstars BTS and John Lennon to smaller acts like Eve6 and Telefon Tel Aviv, not to mention some random NFTs of Disney IP that seemed to have nothing to do with music.

The premise was apparently that HitPiece would auction off the NFTs, then hold the funds in some sort of escrow while it waited for the artists to claim their share of the wealth. Twitter responded as expected, with righteous anger and indignation. And the tech company responded as expected, by saying “Clearly we have struck a nerve…” on social media and replacing the live site with a message on the homepage that simply reads, “We Started The Conversation And We’re Listening.”

And while cringe is as cringe does, it can’t have been sheer cluelessness that drove HitPiece off the cliff. The reality of the online music world we live in is that it was all built on stolen IP in one form or another. There was once no way that labels were going to let MP3s be sold online until Napster forced their hand into letting iTunes firesale songs for 99 cents. Then along came Spotify, whose CEO Daniel Ek worked in the Swedish torrent “industry” before making the labels an offer they couldn’t refuse . Early MP3s on Spotify’s beta even contained metadata that tied the files to The Pirate Bay.

And it’s not just music. YouTube did the same for video, letting users upload copyright content galore before cracking down, kinda, once it got too big to fail. Facebook was started in a Harvard dorm when sophomore Mark Zuckerberg right-clicked the photos from the school’s online student directory for his own version of Hot Or Not. The company would later pioneer the “not a media company” defense to shield it from liabilities while the DMCA gave tech companies a “safe harbor” from copyright offenses as long as there was something resembling takedown protections in place.

It’s all resulted in an ask forgiveness, not permission paradigm that forces startups, well-meaning or otherwise, to try to stay under the radar of lawyers and regulators for as long as possible, then sprint to scale and offer rightsholders a sliver of the pie they could never have baked without stealing the ingredients. So it appears to be happening again in Web3. Only a lot more people appear to be paying attention.

The difference, at least in theory, is that Web3 tooling will bypass centralized platforms and build a flea market of IP stalls run by artists and communities. What gets sold in those stalls remains to be seen. NFTs clearly aren’t slowing down. Coachella just entered the space with lifetime tickets attached to their offering, Baccardi has partnered with Sturdy.Exchange to support female musicians with NFTs tied to song royalties, and Julian Lennon is auctioning off an “audio-visual” NFT of Paul McCartney’s handwritten “Hey Jude” lyrics while keeping the original in his personal possession. We can debate about the value of that last piece of digital memorabilia, but it has to at least be as much as a bootleg “What Would Fugazi do?” sticker on Etsy. Both are going to be available online for the foreseeable future.

There are plenty of reasons to be wary of the music NFT space. Even well-regarded players from Opulous to Ozzy Osborne are stumbling, the former being sued by Lil Yachty for raising VC money on his likeness and promise of “exclusive NFTs” (Opulus says it was authorized) and the latter accidentally enabling a phishing scam that stole thousands of dollars from buyers of his Cryptobatz NFTs.

Artists wishing to opt-out of the whole Web3 phenomenon can claim HitPiece as another appalling example of “NFTs bad!” But that’s the equivalent of looking at contraband Neil Young refrigerator magnets on Etsy and calling for an end of all music merch.

The only thing that can stop a bad guy with an NFT is a good guy with an NFT.

Want to collaborate with Chris & Josh? Contact us.

TAKEAWAYS

Salient statements from this week’s music news.

1. Twitch Partners With Indie Music Licensing Group Merlin

After striking similar deals with the majors, Twitch is trying to get independent acts to see the platform as an opportunity.

Takeaway: Twitch appears to be seeking a middle ground, establishing preliminary deals that stop short of full music licensing agreements.

2. Universal Is Wiping Unrecouped Balances for Heritage Artists

UMG has joined Sony and Warner in forgiving old artist debt while revenue from catalog streaming continues to rapidly grow.

Takeaway: Ever since streaming began to take off, many artists and songwriters have complained that they see low (or sometimes even no) regular royalties from major rightsholders – as these artists/songwriters are still paying off advance checks that they accepted decades ago.

3. Why the ‘Euphoria’ Teens Listen to Sinead O’Connor, Tupac and Selena

You can now watch the transgressive teen HBO series for the tunes.

Takeaway: For those not already in the know, “Euphoria” can also function as a recommendation engine for a new generation, like the films of Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino that it’s constantly nodding to.