In an early chapter of his 2012 book, How Music Works, David Byrne spells out the history of music starting with the time before recorded works became the primary mode of consumption by writing, “Before recorded music became ubiquitous, music was, for most people, something we did. Many people had pianos in their homes, sang at religious services, or experienced music as part of a live audience.”

A few pages later, the iconoclastic former Talking Heads frontman makes his position on the shift to recorded music clear. “I tend to agree that any tendency to turn the public into passive consumers rather than potentially active creators is to be viewed with suspicion.”

So one can assume that Byrne would be pleased with the recent trend — accelerated by the pandemic — of people of all ages learning to make music for themselves by embracing the relative ease of entry into digital music production or utilizing access to unlimited online resources to learn to play physical instruments.

But unlike the pre-phonographic era referenced by Byrne, there is no such thing as an amateur musician in 2021. The “creator economy” has made it possible for anyone who makes or performs music (or dances, or plays pranks, or puts on makeup for that matter) to at least have a chance of making some money for their efforts.

These payouts pale in comparison to the extreme wealth being generated by the platforms that facilitate all of this creating, but it has undoubtedly altered the expectations of most home music makers. It also affects the output of at least some of the more tech-savvy musicians who create with not just the audience in mind, but also the algorithms of a few major tech platforms that offer entré to potentially millions of users.

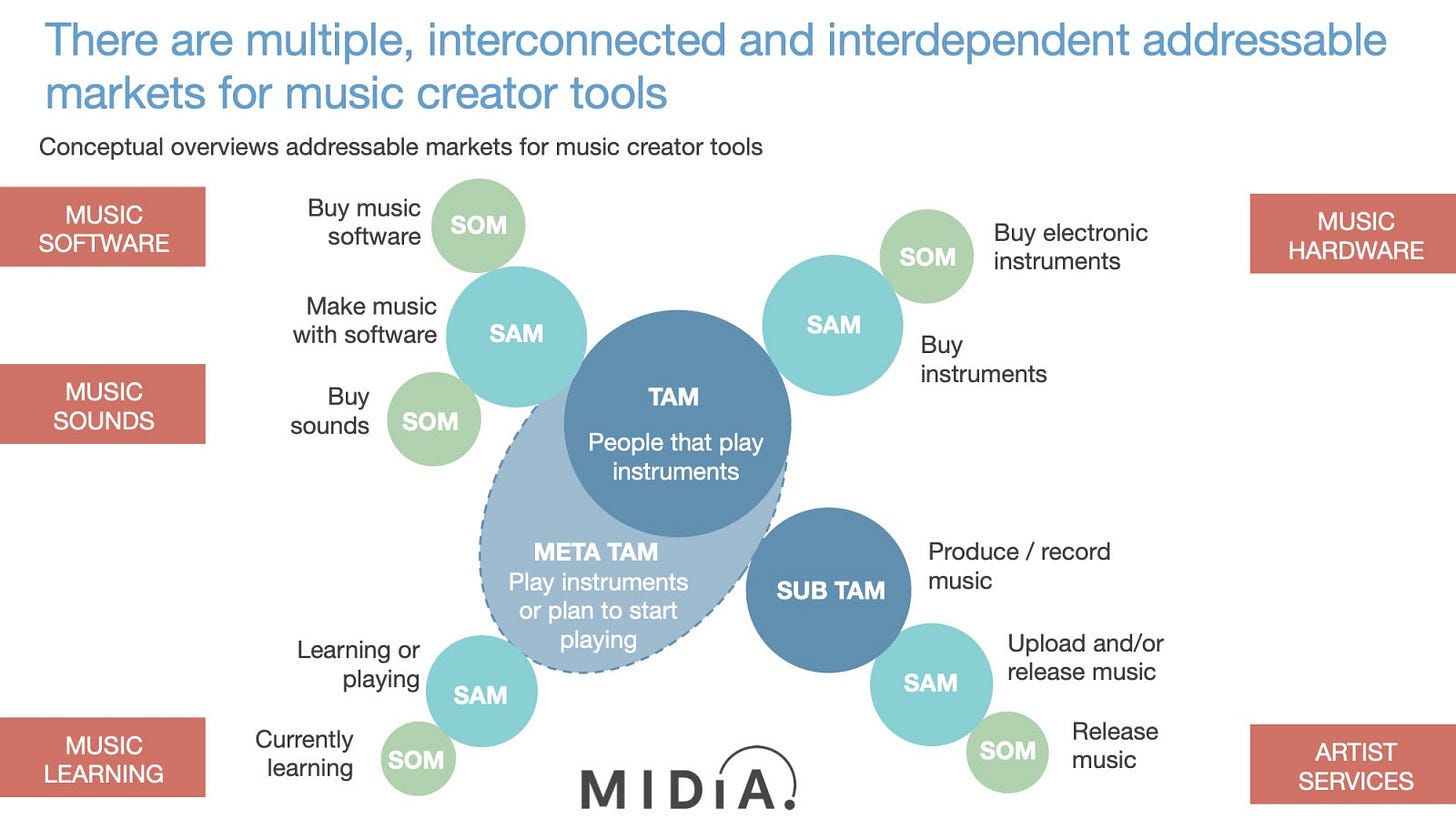

Tools that enable this music creator economy aren’t just consolidated on the output side. Facilitators of the inputs — creator tools — are also experiencing the type of growth, investments and mergers that can be expected in any industry when the wind is to its back. Sweetwater broke $1B in sales for the first time in 2020. Investment firm Francisco Partners acquired Native Instruments from Investment firm EMH Partners in January. Fender bought Presonus last week.

None of these changes are good or bad in essence, although if you’re reading this, odds are that your general disposition is that more music makers > fewer music makers. The caution comes, however, when more and more individuals enter the creator ecosystem with the expectation that it will offer a financial return.

The music industry is already a zero-sum game with almost all of the headline-making growth concentrated at the top. No matter what progress might be made towards equity, there is no way it will be able to keep up with the tide of new musicians entering the space. If the Buddha was right that the wanting mind is the source of all misery, then there could be a lot more dissatisfied musicians in the future.

Or maybe this is a pessimistic view. Because, unlike most human endeavors where those on the lower rungs feel crushed by those above, the innate pleasure of making music and having it enjoyed by even a small audience can be incredibly satisfying. In a recent conversation with DJ Scam, the drum & bass producer was more than pleased that his music-making hobby that dates back to the 1990 has lately found an audience of “a couple dozen weirdos in the UK” via Bandcamp.

This atomization of the audience could be the future of most musicians, and in that sense, it represents a return to the time of pre-mass media. A time when listeners gathered around the piano the same way fans today log in for a Twitch stream. It might be time to downsize the 1,000 true fans concept to 100 true fans, with the audience intimately connected via Web3 communities that support the music-makers the way a church might fundraise for its choir.

Whoever can rightsized expectation to help musicians feel at home, versus standing at the bottom of an impossibly tall mountain of fame and fortune, will thrive in the coming years.

Want to collaborate with The Cadence? Contact us.

TAKEAWAYS

Salient statements from this week’s music news.

1. Twitch Announces Programme to Help Music-Makers Navigate the Livestreaming Thing

The Amazon-owned platform is accepting applications for an incubator to learn the “livestream playbook for music.”

Takeaway: Some artists have found audiences on the platform and are now monetizing their live streaming activity, though plenty of other music-makers who have dabbled with Twitch have struggled to gain any traction on the service.

2. How Environmentally Damaging Is Music Streaming?

Carbon emissions from recorded music formats have increased 45% in the past 40 years due to increased music streaming far surpasses the environmental benefits of not manufacturing physical products.

Takeaway: Listening to an album via a streaming platform for just five hours is equal in terms of carbon to the plastic of a physical CD. The comparative time for a vinyl record is 17 hours.

3. How Hits by Drake, Ye & More Get Released Before Songwriter Pay Splits Are Settled

When negotiations overrun release schedules, more artists are asking for forgiveness instead of permission.

Takeaway: The decision to release a song without finalized publishing splits is often made by the performing artist’s label to meet a timely release schedule, but the ramifications of the hastened release are felt by those in the publishing ecosystem most and can lead to royalties being withheld from songwriters, or, in some extreme cases, lost altogether.